Color-coding your scrum board

At my company we've been using Scrum for a few years now. And even though I'm quite sure we're not living up to Schwaber's and Sutherland's standards, we seem to have found a way to make the process work for us across many projects.

Like many companies we started out with a simple physical scrum wall:

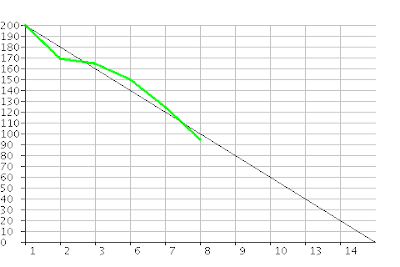

Later we started putting the burndowns on our intranet, so that everyone could see them. And we started using colored post-its for indicating different types of work.

In our case we use yellow for development tasks, pink for non-development tasks (i.e. testing and documentation) and orange for defects. There's no specific reason for using these colors. They just happened to be the post-it colors we had available when we started using colors. Since then my mind got used to them and I haven't yet heard a reason to switch. Although some of our tech writers are frowning at being "the guys who do the pink work".

As we've been growing our use of Scrum, we've also been using more and more tools. First was the online burndown charts. And then we started using a virtual scrum wall, so that we could share the same wall between distributed teams. It was a great boost for our distributed development, although most team members still sometimes long back for the days when they had a physical wall. Nothing beats the satisfaction you get from moving a physical post-it across 5 inches of whiteboard space.

We've been using Scrum for Team System for a while now to keep track of our stories and tasks. And I thought we were quite happy with it. Sure, we lost the ability to color code our task types. But the task board we used has nice colors too, although it uses them to code the columns. So "done" is green, etc.

But recently I noticed that it was difficult to quickly understand the status of a sprint from simply looking at their board:

So is the status of this project? It's hard to say without looking at the details of each task. It could be that everything is going fine, it could be that things are horribly wrong. There is no way to tell which one it is, unless you get closer to the board and read.

So over the weekend I re-encoded one of our boards with the colors we used back in our "physical days". Now look at the same board where we've used colored post-its:

Yellow = development tasks, pink = non-development tasks, orange = bugs

When we applied this color coding to our existing scrum board, I was shocked at the amount of insight it could add.

So I wrote a quick tool to generate these color-coded task boards for us. The process is purely automatic: read the data from team system, apply a few simple rules (e.g. anything with the word "bug", "defect" or "issue" in it, must be a defect) and output a HTML version of the data. But even with such a simple system we've been able to more easily get a feeling of where all projects stand by simply glancing at the board.

So what is your experience with scrum walls? Do you have any tricks you use to help visualize the data?